Background

The Basin’s Natural Resource History

Photo of of Crystal Lake Courtesy of the Coeur d’Alene Casino

Photo of of Crystal Lake Courtesy of the Coeur d’Alene Casino

The earliest recorded history describes the Coeur d’Alene Basin as a pristine land abundant with life. The natural riches surpassed the beauty we currently see. An excerpt from a report done by the National Research Council of the National Academies regarding our area reads:

The river was described as “transparent as cut glass,” the mountains “clothed in evergreen forests” of white pine, grand fir, douglas fir, and spruce; the riparian areas thick “with the cottonwoods and silver beeches on both banks almost forming an arch overhead” of the deep channel; and the stream “alive with trout and other fish” that could be seen by the thousands in the clear water” (Rabe and Flaherty 1974).

This abundance provided the sustenance for the Coeur d’Alene Tribe who inhabited the Coeur d’Alene Basin since time immemorial. Fish and plant life were staple foods for the original inhabitants of this region. These natural resources would also be utilized by the earliest non-indigenous residents as well.

![]()

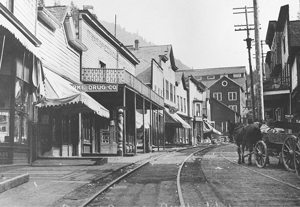

In 1883, precious metals were discovered, and silver mining would become a staple industry. Mining provided a booming economy for our area, especially for incoming prospectors and their families. In fact, the South Fork area of the Coeur d’Alene River would eventually produce more silver than any other area in the world and would eventually take on the name, Silver Valley. This industry created a strong legacy that continues today.

|

|---|

![]()

For over a century, the communities would see some harmful impacts of mine-waste contamination on the environment. In 1983, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) listed the Coeur d’Alene Basin on the National Priorities List (NPL). While the EPA would focus on addressing contamination as it relates to human health, the NPL listing would open the door for the Natural Resource Trustees to begin the Natural Resources Damage Assessment Process. |

|---|

In 1991, the Coeur d’Alene Tribe would be the first natural resource trustee to initiate a lawsuit under the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act as well as the Clean Water Act against the parties responsible for natural resources degradation. They would be joined by the U.S. Department of Interior and the U.S. Department of Agriculture in 1996 and the State of Idaho in 2011. This was done with the intention of restoring the natural resources in the Coeur d’Alene Basin. |

|---|

![]()

In September of 2000, the Trustees finalized the Report of Injury Assessment and Injury Determination. This document would become foundational as evidence of harm done to natural resources as a result of mine-waste contamination. It was an exhaustive scientific report citing dozens of studies relating to surface water; groundwater; bed, bank, and shoreline sediments; riparian and floodplain soils; aquatic biota, including both fish and aquatic invertebrates; wildlife, including birds, mammals, reptiles, amphibians; and vegetation.

|

|---|

![]()

The last of the major settlements was reached in 2011. The Trustees, working together under a Memorandum of Agreement, began the framework for the development of a restoration plan to kickstart the restoration process. The Trustees launched the Restoration Partnership shortly after in order to effectively engage the public in restoration efforts. Public Scoping for the development of the Restoration Plan began June 13, 2013 and ended on August 27, 2013. |

|---|

The Coeur d’Alene Basin

The Coeur d’Alene Basin includes all the land that drains water into Coeur d’Alene Lake and out the Spokane River. It encompasses approximately 2.4 million acres of mountainous terrain with numerous streams, rivers, and lakes. It starts upstream to the east near the Montana border. Here, the South Fork Coeur d’Alene River flows through what is referred to as the ‘Silver Valley’. It then converges with the North Fork Coeur d’Alene River at Enaville, Idaho and becomes the Coeur d’Alene River mainstem. The Coeur d’Alene River mainstem continues to flow west through the chain lakes until it reaches Coeur d’Alene Lake.

From the south, the Coeur d’Alene Basin includes the St. Joe and St. Maries rivers. These rivers converge in St. Maries, Idaho and become the St. Joe River mainstem. The St. Joe River mainstem flows northwest for approximately 20 miles where it flows into Coeur d’Alene Lake.

Coeur d’Alene Lake is the main body of water in the Coeur d’Alene Basin. It flows north to its outlet, the Spokane River, at Coeur d’Alene, Idaho.

Mine waste contamination primarily affects the South Fork Coeur d’Alene River, Coeur d’Alene River mainstem, and Coeur d’Alene Lake. There are also areas in the Spokane River that have deposits of contamination. Therefore, the upper Spokane River is included in the description of the overall Coeur d’Alene Basin area.